生日快樂, 小牛! Happy birthday, Jules! These were the first things Jules heard when he woke up this morning as an eight year old. He had his favorite breakfast of a croissant, yogurt, fruit and juice before heading to the city of Xi’an two hours away by bullet train. Since it was his birthday, there were no adult scheduled trips to historical sites, museums, etc. and instead, we followed Jules’ lead. This, of course, involved an afternoon at the arcade and an Italian/pizza dinner at a wonderful restaurant called ‘Cyclist Restaurant,’ which I would wholeheartedly recommend if you ever find yourself in Xi’an and are tired of Chinese food. Whaaaa?!? Tired of Chinese food?!? I’m drooling just thinking about the food in Xi’an right now, sigh.

The next morning we had an early start with our tour guide, Jenny, and her driver to beat the crowds to see the world-renowned Terracotta Warriors (秦陵兵马俑). It’s hard to put into words my feelings as we entered the airplane hangar-like building housing the warriors. If you’ve ever found yourself in Chinatown right before Chinese New Year’s at a supermarket, and all of a sudden, someone announces over the loudspeaker that they’re giving away $8 off coupons, then you’ll know half of what I’m talking about. In order to get a frontal view of the warriors, it was a no holds barred event, neither children nor the elderly were spared. A few strategically placed elbows later (totally necessary, BTW), we found ourselves face to face with one of the most remarkable and, unfortunately, tragic sites I’ve witnessed.

Starting around 200 BC, Emperor Qin Shi Huang, who was then 13 years old, had hundreds of thousands of workers, i.e. slaves, work for almost four decades to complete his mausoleum. These warriors, along with horses, chariots, musicians, etc. were supposed to then accompany the emperor in his afterlife. Once the workers had completed their task they were then killed, since the emperor was afraid they would reveal the blueprint to future tomb raiders.

What makes this site so remarkable, besides the sheer size of it, is the craftsmanship involved. I couldn’t believe the details found on each soldier, where you can see the lines of hair and treads on the soles of the shoes. Unbelievably, no two soldiers are exactly alike. What is also amazing is the fact that only three pits out of hundreds have been excavated. Like the laborers who suffered and died making the Great Wall, it saddened me to think that grand works such as this one had to come at such a cost.

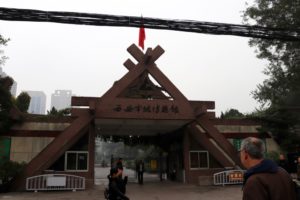

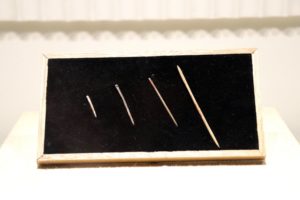

After a somewhat vigorous morning at the Terracotta Warriors, it was nice to change course and spend a peaceful afternoon at the underrated Banpo Neolithic Village (半坡博物馆). Built around 4000 BC, this village from the Neolithic period, representing the Yangshao culture, really struck me as quite modern. The architecture of the homes was sturdy and utilitarian based on simple geometry concepts, ‘bathrooms’ were not located inside the homes and needles were found, suggesting woven garments. Also, women ran the show and made the executive decisions for the village. There were no ‘marriages,’ as men were used for booty calls, and then the women would all take care of the children as a collective whole. How anthropologists reached these conclusions based on some ruins boggles my mind, but it’s certainly a riveting theory. It’s also of note that in this matriarchal society, few ‘weapons’ were found, and in place of animal or human sacrifices historically found in graves, assorted pieces of pottery were used to stand in the place of live offerings. Progressivism, anyone? Also, in a sweet, albeit macabre, way, a body part of the deceased would be kept in a jar in the family’s home, so the deceased would always be close to his/her family. A finger of a living relative would also sometimes be cut off to be placed in the tomb with the deceased.

Until afterlife do we part….