Not ready to head back to the hustle and bustle of city life just yet, we spent the next couple of days at Yen Duc Village, a community-based tourism retreat set amongst rice fields and farms an hour west of Ha Long City. It’s working on obtaining US/EU organic certification at the moment (a rarity in Vietnam), employing around 70 locals. We were not prepared for how much we would love our experience in this area and with its people.

First of all, our super kind and warm guide, Gi, told us that we were the only guests staying for the two days, so guess what? We had an entire village to ourselves! The retreat is set in the middle of a small, local town (Yen Duc Village) with only four guest rooms, so guests have a chance to interact with local life on a more personal level. From learning how the villagers farm and fish to having conversations with locals, like Ms. Mung Tho, we left with a better understanding of a country that employs more than half of its population in agriculture.

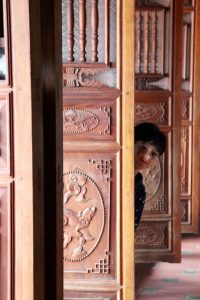

Ms. Mung Tho’s husband passed away, but his family owned the home we visited for the past 150 years. The woodwork was all original, and we were given a chance to have tea with Ms. Tho and visit her home. The relative lack of windows, high ceilings and wooden beds were all designed as adaptations to the Vietnamese heat and humidity. Ms. Tho showed us the extensive family tree and told us that the Vietnam War, or American War as it’s known in Vietnam, destroyed most of Yen Duc Village, sparing her and her husband’s home.

Sobering thoughts stayed with Philip and me as we rode our bicycles with Gi through the village, seeing the many rice farmers bent over planting their seedlings by hand, one by one, in the rice paddies from dawn until dusk. This is seriously back breaking work, and we found out that these rice farmers tend to retire early and take on other jobs later due to the physical toil it takes on their bodies (I was certainly thinking about these farmers while barking at Jules to finish all the rice on his plate tonight).

We rode back to the village to learn how grown rice dried on the stalk is then processed by hand to remove the husk and to separate the bran from the white rice. The next activity was probably the most fun, and most scary, for Jules. Gi took us to a pond to hunt for our dinner by showing us how to catch fish by hand using funnel-shaped bamboo baskets. We donned our waders and rubber gloves and randomly placed our baskets in the murky water, hoping to catch a fish and not get sucked down by the mud underneath. What kind of futile task is this?? Before we knew it, Philip managed to catch two fish! After trapping the fish, you had to reach your hand into the hole on top of the basket to grab the fish by the body (not like I could really control what I was grabbing, mind you) to place into the collecting tub. Let me tell you, this was no easy feat. I was able to grab one, but Jules had a tough time with it, worried that the fish would bite him. We were very grateful for the fishes’ lives as they were delicious fried up for dinner later.

After dinner, we were shown how to make banh troi, or floating rice cakes, which were introduced by the Chinese. Gi enjoyed using Philip’s nickname for Jules, “monkey,” and happily showed “monkey” how to make these white orbs of sticky rice flour filled with mung beans and palm sugar, rolled in toasted sesame seeds. The banh troi are boiled until they float to the top, and then they’re added to a bowl of boiled water, palm sugar and ginger. Such an elegant dish with delicate flavors. Soon after, we all fell out to the rhythm of frogs croaking in the nearby rice paddies.

The next morning started with my replenishing bowl of pho for breakfast. If only I could make a proper pho broth, then I would seriously consider having this as breakfast every day. Like Chinese congee, it really provides a good combination of protein, carbs, veggies and liquids. But, this post isn’t about pho. Don’t worry, that’s coming up in a later post.

We hopped back onto our bikes and headed to the local farmers’ market. I have to say, Asian farmers’ markets rule. Not only can you stock up on fruits and veggies, but you can have an entire pig or chicken cut up fresh for you, there are dried goods, seafood of every kind, sweets and even paper outfits/cigarettes/iPads for your ancestors. With the Lunar New Year right around the corner, some of the market stalls were selling the usual Lunar New Year wares I’m accustomed to seeing — red envelopes, lanterns, paper money, etc. In Taiwan, paper money is burnt during the new year as a way of providing money to your ancestors in the after world. In Vietnam, I learned, not only is paper money burnt, but you can burn just about anything imaginable to offer modern conveniences to your ancestors (see the perfume, gold watch and iPhone above). Even Gi was laughing at some of the new offerings this year, including fancy sports cars, expensive lingerie and the latest electronics.

With the Lunar New Year right around the corner, some of the market stalls were selling the usual Lunar New Year wares I’m accustomed to seeing — red envelopes, lanterns, paper money, etc. In Taiwan, paper money is burnt during the new year as a way of providing money to your ancestors in the after world. In Vietnam, I learned, not only is paper money burnt, but you can burn just about anything imaginable to offer modern conveniences to your ancestors (see the perfume, gold watch and iPhone above). Even Gi was laughing at some of the new offerings this year, including fancy sports cars, expensive lingerie and the latest electronics.

Some of the vendors were quite taken with Jules, since ‘mixed blood’ kids are seldom seen in this area. A couple of the vendors were convinced that I was part Vietnamese. Interestingly, just the other day I found out from my aunt that my mom had her ethnic DNA analyzed, and it turns out that the majority of her ethnic origin is of Chinese and Vietnamese descent while the rest is Japanese. Hmm, maybe I’ll have to send in a little saliva-in-a-tube sample myself.

Next, Gi put us to work by visiting a retired rice farmer who at 80 years old specializes in making brooms by hand from leftover rice stalks once the rice has been harvested. Her great granddaughter Sou, a delicious little two year old, took an immediate liking to Jules and planted kisses on his cheek while he tried to look like a nonchalant, cool 8 year old. I think he secretly liked it. We learned how to twist the stalks around to make them stronger, and we left with our own little broom. Another thing I’ve noticed since living in Taipei is how the collection of leaves and clearing of sidewalks is still done by handmade brooms instead of the angry, high-pitched screams of leaf blowers…ahhhh.

We returned to the village for one last meal before saying goodbye to this special place and to the wonderful Gi to catch a performance of the Yen Duc Water Puppet Show. Vietnamese water puppetry is unique, because it is performed entirely on water without any of the controls or puppeteers visible. The puppets are made of wood and then heavily lacquered for waterproofness and for the vivid colors that lacquering provides. Philip and I were charmed by the expressiveness of the puppets, but our ‘cool’ 8 year old thought the show was boring. A few days later, though, guess who suggested that we create our own version of a water puppet show by telling the story of the Chinese zodiac animals? Yep, he’s still our baby.